Adult Drowning Deaths Are Increasing. Swimming Lessons and Reduced Alcohol Use Could Prevent Them

August 27, 2024

4 min read

Adult Drowning Deaths Are Increasing

Most fatal drowning incidents in the U.S. involve adults, not children, and they often involve alcohol

More than 4,500 people in the U.S. lost their lives in drowning accidents in 2022, the most recent year for which data are available, and more than 70 percent of them were adults. There have been several notable adult drowning cases this summer, including a beach incident in Florida that killed three young men in June and a river tubing accident in Oregon that killed award-winning chef Naomi Pomeroy in July.

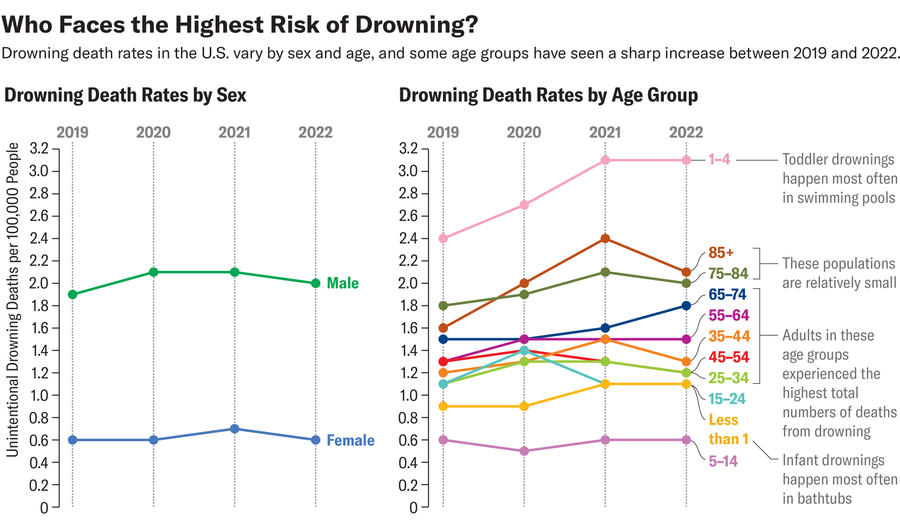

Adult drowning deaths have been increasing in the U.S. A recent report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that unintentional drowning death rates increased in almost every adult age group between 2020 and 2022, when the COVID pandemic led to pool closures and lifeguard shortages.

The increase “was concerning because drowning death rates in the United States had been decreasing for the last two decades,” says Briana Moreland, a CDC researcher, who co-authored the report. The reasons behind the trend aren’t totally clear, but as noted in an earlier report from the agency, people spent more time recreating outside during the pandemic, and boat sales increased. Learning more about the factors that contribute to adult drownings could help researchers develop better prevention strategies.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Despite the higher incidence, adult drownings tend to receive far less attention than childhood cases do, in part because toddlers have the highest drowning death rates in the U.S. Drowning prevention campaigns typically focus on promoting children’s swimming lessons and feature photographs of young children in swimming pools. “Drowning prevention has been entirely too focused on the child, and that’s a weird thing coming from a pediatrician,” says Linda Quan, a pediatric drowning expert at the University of Washington. “It’s terrible to lose a child, but it can also be devastating for a child to lose a parent. It affects the whole family.”

One factor that differentiates adult and childhood drownings is the water sources involved. While young children are more likely to drown in bathtubs and swimming pools, most adult drowning incidents occur in natural bodies of water, such as rivers and the ocean, which can contain hidden dangers, including currents and steep drop-offs, even when they appear calm. “Every natural waterway is different,” says Adam B. Katchmarchi, CEO of the National Drowning Prevention Alliance, a nonprofit that studies and promotes water safety. “Sometimes we underestimate the power of water. And as an adult, it’s easy to think that nothing bad will happen.”

Adult drowning incidents also frequently involve alcohol, which can impair judgment and coordination. “If you’re intoxicated, and you fall into water, your ability to coordinate your breathing and muscular movements will certainly not be as crisp as it is when you’re sober,” says Stephen Hargarten, a professor of emergency medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin, who has written about drowning. Operating boats while under the influence of alcohol is already illegal in the U.S., and alcohol is banned at many public beaches, too. Nevertheless, alcohol remains the leading factor associated with fatal boating accidents in the U.S., which killed 564 people last year—most of them by drowning, according to the U.S. Coast Guard.

Another factor that affects how adults behave around water is their perceived swimming ability. For example, studies by Quan and other researchers have found that many boaters think that only inexperienced swimmers need to wear life jackets. Men are especially likely to rate themselves as capable swimmers, but the recent CDC report found that fewer than half of U.S. male adults had ever taken a swimming lesson.

Understanding male drowning deaths is important because male individuals are the most at risk in every age group, accounting for about 75 percent of unintentional drowning deaths in the U.S. Evidence suggests that men and boys are more likely to engage in risk-taking behaviors in general. This increases their likelihood of dying from causes of injury deaths besides drowning, such as motor vehicle crashes. But misperceiving their swimming abilities may also prevent them from accurately determining their risk level around water. A New Zealand-based study published earlier this year found that male adults consistently overestimated how far they could swim, particularly in natural water sources. Perhaps most concerning, many of the male study participants continued to overestimate their swimming abilities even after a field test revealed their deficiencies.

Swimming skills alone can’t prevent a person from drowning. Experts at the American Red Cross and otherorganizations call for additional layers of protection, including lifeguards and life jackets. Still, swimming lessons provide an opportunity to teach children and adults about water safety issues, such as natural water hazards, as well as the traditional swimming strokes. The U.S. National Water Safety Action Plan, which was released by an interdisciplinary coalition of experts last year, recommends improving access to swimming and water safety training for all age groups, particularly among populations, such as Native American, Alaska Native and Black people, who have disproportionately high fatal drowning rates as teenagers and adults. “Our message is that swimming is for everyone,” says Katchmarchi, who helped draft the plan. “These skills are relevant to everyone’s safety.”